What is electrical frequency and why does it matter?

What is electrical frequency and why does it matter?

Keeping the frequency of our power supply constant is a delicate national balancing act that requires changes in under a second.

Whenever you turn on your kettle, phone charger or any other electrical appliance in the UK, the power that comes out is what we call alternating current (AC). That means it is alternating between positive and negative voltage.

This oscillation is known as electrical frequency. Alternating current that oscillates 50 times a second as it does in the UK is said to have a frequency of 50 hertz (50hz).

But why does it matter?

The equipment in your home, factory or office is designed to operate at 50hz within a tight tolerance so it’s very important to keep the frequency of our power supply stable.

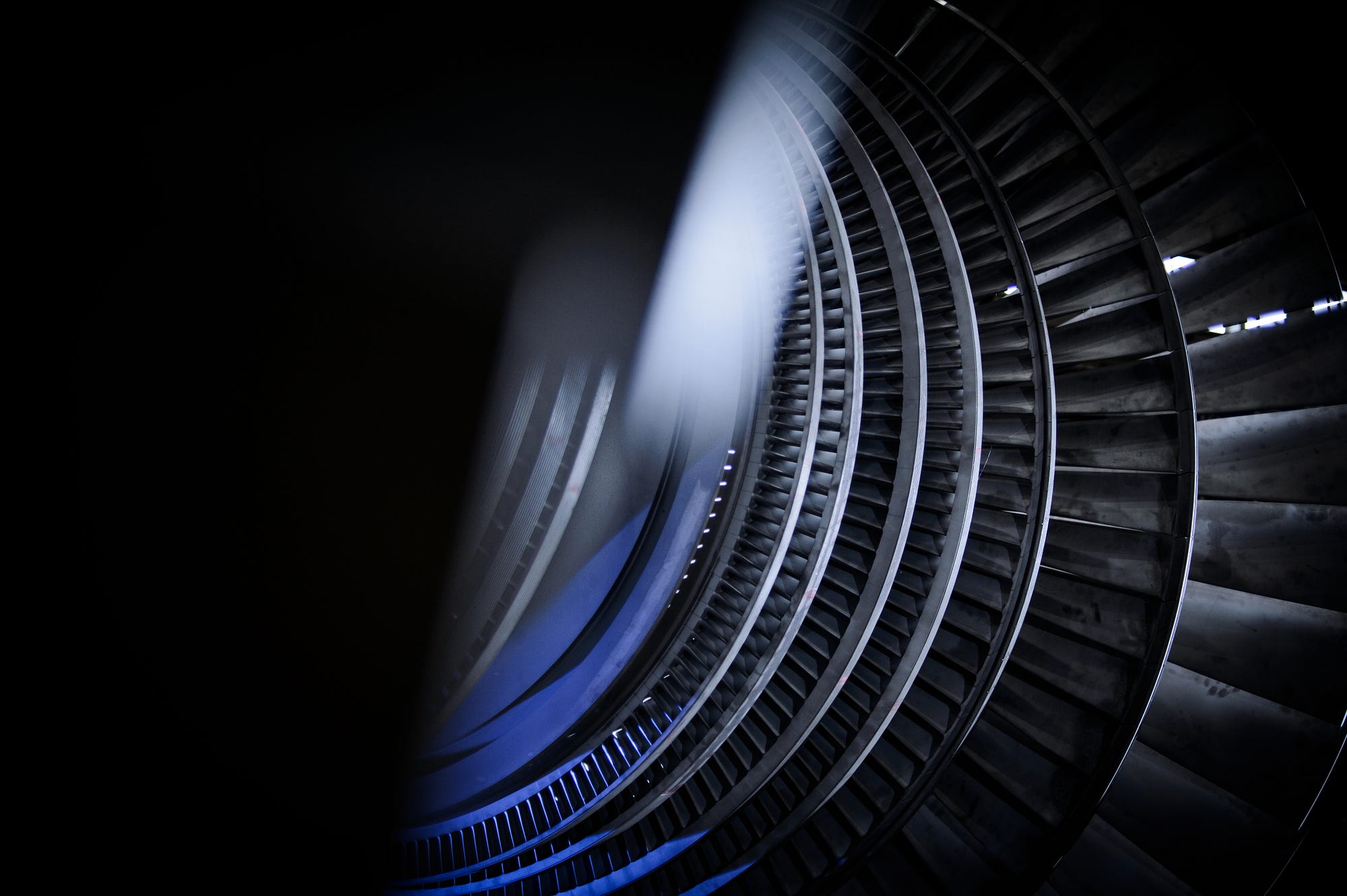

That’s why every generator in England, Scotland and Wales connected to the high voltage transmission system is synchronised to every other generator. They are all locked together, spinning at 50hz, to form a single, stable supply.

How is frequency managed?

Changes in supply and demand for electricity can have a major effect on the frequency of the grid. For instance, if there’s more demand for electricity than there is supply, then frequency will fall. Or if there is too much supply, frequency will rise.

And the margin for error is very small. In fact, any power with a frequency as little as one per cent above or below the standard 50Hz risks damaging equipment and infrastructure if it persists. You can see how far the country’s frequency is currently deviating from 50Hz here.

In the UK, the job of managing electrical frequency falls to the National Grid. To ensure stability, the Grid contracts power generators like Drax power station to provide frequency response services, so when frequency changes on the grid, Drax’s generating units can automatically respond.

If the frequency rises, the turbine reduces its steam flow. If the frequency falls, steam flow will increase. In the case of generating units at Drax power station that response bursts into action less than a single second from the initial frequency deviation.

Frequency future

Not all power generation technologies are equally suited to helping balance Britain’s frequency. Intermittent technologies such as solar or wind are more difficult to control than units at thermal power stations, which can be dialled up or down so simply and so fast.

National Grid is currently reviewing how best to source services such as frequency response to match Britain’s evolving electricity network. They face two challenges: fewer conventional generators being dispatched by the energy market, and an increasing requirement for fast-acting frequency response. The ideal scenario is one where services can be increasingly sourced from reliable, flexible and affordable forms of low carbon generation along with other necessary system services such as inertia, reactive power and black start.

Read the full story on why we need the whole country on the same frequency on Drax.com.